Hung-to-the-over and clutching at a bottle of warm Coke, I sat through most of Alien 4 today. It’s not a good movie, but it’s more interesting that the previous two in the Alien franchise (none of them come close to the original’s shock and awe). The director, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, plays it for laughs, insofar as a movie about chest-bursting aliens can be funny. Heroine Ellen Ripley has been reconstructed from a blood sample of her former self, along with an ickle baby alien insider her (“Oogie-woo, who’s a pretty boy? Don't bite. It's rude.”) The monster is removed surgically and allowed to grow into a Queen. The Queen retains Ripley’s ability to reproduce in the mammalian manner (ie, the father is down the pub throughout) and gives birth to a bouncing baby boy – who then kills his alien mother with a mean right hook. Ripley, understandably conflicted, then kills her “son” by burning a window open with her acidic blood and flushing him out into space. If all this didn’t take place in the year 2525, it could easily be a Greek myth. There’s certainly the right amount of incest and matricide.

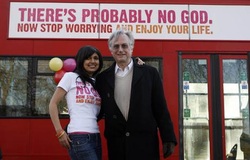

Incredibly, there’s a moment in Alien 4 when an android sees a crucifix and crosses itself. “Are you programmed for that, too?” asks Ripley. Crucially, no – for we learn that the androids have been gifted free will by their creators. One of the themes of the Alien series is how man is surpassed by the things around him. He is outlived and outpaced by animals and by even the robots that he built. That the android believes in God suggests that life doesn’t begin and end with man. Ripley is a zombie, but the android is alive and – as Ripley points out – more compassionate and therefore more “alive” than her human colleagues. Even the aliens have started to surpass us. When Ripley’s oozing baby is born, we glimpse the future. Who knows, perhaps even the chestbursters will one day sing “Nearer My God to Thee” as they fly merrily from their eggs? Androids believe in God, but scientists don’t: or at least geneticist Richard Dawkins says he doesn’t. Or does he? He can’t be sure… In a debate with Rowan Williams this week, he admitted that he is an agnostic. Dawkins said that he is only “6.9 out of seven” sure of the absence of God but that “the probability of a supernatural creator existing is very very low.” I’m surprised at the level of surprise that this statement has garnered, for he has indeed insisted many times before that he can’t dismiss the possibility of God. But what is surprising is that Dawkins can consider that possibility and then so quickly disregard it. For the possibility of God existing is far more mind-blowing than the likelihood that he does not. I don’t want to make the case for Pascal’s Wager being a determinant of faith. “Betting of God” is a shallow approach to religion and isn’t what motivates anyone but Pascal to follow one. But it’s also an odd reason to discount the existence of God, too. When it comes to theology, probability and consequence are not proportionate to another. The probability of God existing might be low but the consequences if he does are high. Vice versa, the probability of God not existing might be high but the consequences of that outcome are very low. Consider the calculations that a man makes when insuring his house from fire. If the chances of his houses catching fire are just one-in-a-hundred, he might forgo purchasing insurance because he gambles that he’s unlikely to ever need it. Yet all of us would still make the purchase because the consequences of that one-in-a-hundred accident happening are so unbearably dire. A single, improbable spark could destroy everything. Therefore, the man buys the insurance. If Dawkins is playing the law of averages, then he has to make the same calculation about God. To be sure, he only acknowledges a 1.5 percent chance that the Almighty exists. If his gamble is proven right, then Dawkins will die and suffer no consequences. But if that 1.5 percent chance comes through, the consequences are hugely disproportionate to the stakes. One of the reasons why I go to Church is that I don’t want to run the risk of spending eternity in Hell with Richard Dawkins. Even a 1.5 percent risk isn’t worth running. To re-emphasize, I don’t want to push Pascal’s Wager – but it does strike me as odd that if an intelligent man would concede that there is a 1.5 percent chance that something is true (especially when something has the weight of 2,000 years of civilization behind it), he wouldn’t explore it more seriously. It’s even odder that he thinks there is a greater possibility that there’s life on other planets. But what would it mean if that life worshiped God, too? What if the Predator is a Methodist? Or the alien is a Seventh Day Adventist? What would Dawkins say if he opened the front door and found a dalek clutching The Book of Mormon? If he wants to get rid of him, the easiest answer is, "I'm sorry, I'm a Roman Catholic..  I will definitely die a Catholic. No doubt about it. A Catholic doesn’t just die – they reconcile. They accept their mortality and submit to the will of God, trusting that he will forgive them for all the evil that they have done. Like the Prodigal son, they come home. I have accepted the teachings of the Catholic Church and I have faith that the Last Rites, honestly sought and validly delivered, will see me to Heaven’s gate. In the final analysis, it is this faith that makes me a Catholic. But I often find it hard to live like a Catholic. Part of the problem is that I am a convert. Going to Mass and sitting through dirge-like hymns, masticated liturgy, and boring sermons doesn’t come naturally. I was raised a Baptist, and although I rejected it in my teens, I am starting to realize what an impact it had upon me. As a personality type, I am a fire and brimstone evangelical. I should stress that theologically I am strictly Catholic. But, o, what I’d give to hear a bit of gospel! A sermon with shouting! A tambourine! A bass guitar! And-a-one-two-three-four – “Majesty! Worship his Majesty! Unto Jesus, be all glory, honor, and praise!” To anyone not born within the sound of righteous clarinets, this probably all seems bizarre. But I was twelve years old when I saw my first demon being cast out. I am cut from a different polyester. Much of modern Catholic culture lacks the certainty that I was raised with. As a child, I was taught that everything you need to know about God and man is found in the Bible. If the Bible had said Newt Gingrich was a virgin, we’d have believed it. Faith was a matter of black and white, right and wrong. Sunday School wasn’t a thoughtful flick through a “moral matters” textbook, it was a trial of fire. God was everywhere, always watching you. Failure to feel His presence was your fault – your lack of faith. There was no slowing down for doubters. The most ubiquitous phrase was “God willing.” It articulated an almost Islamic faith that God was behind every action and consequence. “I’ll pass my exams, God willing.” “I’ll get a job, God willing.” “I’ll be out in nine to ten months, God willing.” God willed it and it was done. And you didn’t ask any damned questions about it. My upbringing made converting to Catholicism difficult – although not in the way that I expected. I accepted the theology totally and without equivocation. But without any ethnic link to Catholicism (my father’s family are Irish Catholics, but totally out of practice) I found it a bit of a culture shock. Baptism reinforces its tenets every day with aggressive proselytizing. Not so Catholicism. Catholicism is a religion of silence and contemplation. That’s fine and understood, but sometimes – and, yes, this is a subjective judgment – the modern Church is a little too quiet for my taste. Bishops, it can feel, prefer tolerance to truth. Many parishes have a limp sociability that papers-over cracks of disbelief. Priests bend over backwards to reassure people of other faiths but are reticent about pushing the validity of their own. Evangelism is a strict no-no. All too often, it is lay people who have to pick up the banner of social conservatism; the church hierarchy seems scared of it. All of this is a long winded way of articulating why I’m so frustrated with polls that show that American Catholics are overwhelmingly in favor of contraception. Public Policy Polling reports that, “There is a major disconnect between the leadership of the Catholic Church and rank and file Catholic voters on this issue. We did an over sample of almost 400 Catholics and found that they support [Obama’s mandate for contraception coverage in Catholic healthcare plans] 53-44, and oppose an exception for Catholic hospitals and universities, 53-45. The Bishops really are not speaking for Catholics as a whole on this issue.” This is the phenomenon of “I’m a Catholic but…,” and it really makes no sense to a former Baptist. No Baptist would ever say, “I’m a fundamentalist but I don’t believe in all of it.” That would be a contradiction and a rejection of faith and might even get you excluded from the church. But in the contemporary Catholic Church, it is something I hear from the laity all too often. It makes no sense. For what is a Catholic except someone who accepts Catholic doctrine? Isn’t that what defines us? There are many complex reasons why the “I’m a Catholic but…” phenomenon is widespread. But a good insight into it is offered in a fine blog post by my friend and colleague Peter Foster. Peter is a Catholic, but he writes in the Daily Telegraph of his dislike of Rick Santorum thus: “I can’t escape the whiff of the witch-hunt about Mr Santorum, who is of a breed of Catholic unfamiliar to us English: a man of the strictest Catholic theology … whose message is transmitted through a distinctly evangelical amplifier … I’m afraid I can’t find much that’s terribly sympathetic or merciful in Mr Santorum, and I’m not sure that’s a particularly good quality in a man who wants to assume the awesome responsibilities of the US presidency.” Peter’s problem with Santorum is partly his opposition to government funded pre-natal testing. Peter concedes that Santorum’s critique is “truthful”, but what disturbs him is the presidential candidate’s tone. He writes, “Perhaps it is because I was brought up as a middle-of-the-road English Catholic – show up on Sundays, eat fish on Fridays (more expensive than meat now, of course) and don’t ever sing the hymns too loudly (that’s a vulgar habit Anglicans have) – that I find Rick Santorum so, um, scary.” I don’t find Santorum scary. In fact, I find his tone on moral matters refreshingly clear. But here is the likely difference between me and Peter. I was raised in an evangelical culture that is largely imported from America. He was raised in a cradle Catholic community that is steeped in the modern Catholic culture of sober reflection and ecumenical goodwill. Yet – acknowledging the cultural differences – I still struggle to empathize with Peter’s reaction to Santorum’s rhetoric. Do you believe that Santorum is right or not? If yes, then what’s the problem? I can’t count the number of times that I’ve sat with Catholic priests, listened to them talk softly about the problems of the world, and wanted to scream, “What do you believe, man?! Identity it, testify it, and let’s save some souls!” But instead, everything is deadened by another cup of tea and a sleepy rosary by the fire. Naturally, there are priests who are thrilling and compelling – men who wage a permanent war on apathy and indecision. But there is, in many quarters, a scent of death about the Catholic Church. We are waiting for our extinction at the hands of barbarians or old age. It wasn’t always like this. My new biography of Pat Buchanan explores an age when Catholics were confident and outspoken. In the 1950s, American Catholics filled whole stadiums to pray for the conversion of Russia. They believed that they were right and they weren’t afraid to say so. Santorum represents a revival of this spirit. I shall close on a quote from Buchanan’s memoirs, Right From the Beginning: “There was an awe-inspiring solemnity, power, and beauty about the old Church, which attracted people who were seeking the permanent things of life … Not only did we proclaim ourselves to be “the one holy Catholic and apostolic Church,” under the watchful eye of the Holy Ghost – with all others heretical – we were gaining converts by the scores of thousands, yearly … Ecumenism was not what we were about; we were on the road to victory. Why compromise when you have the true Faith?” Pray for me during the Lenten season, a sinner also.  It’s the 60th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth’s ascension to the throne. I was born a republican and I suspect I’ll die a republican, but I’ve always admired and loved HRH. Through all the awful things that have happened to Britain in the past 60 years, she alone has survived with her dignity intact. Stanley Baxter (a Scottish comedian) used to do a wicked parody of her icy protocol, asking “Did you come far?” to anyone and everyone she met. A girl presents her with a bunch of flowers – “Did you come far?” A man streaks across the pitch – “Did you come far?” Prince Philip wakes her up with a cup of tea – “Did you come far?” We must be a sea of faces to Her Majesty; unfamiliar and ubiquitous. Her success lies in her passivity, which is the English genius. Long after the bombs have fallen and the Caliph has triumphed, there will be a small group of English tourists at the feet of the Sphinx drinking tea in the midday sun. People scorn us for our lack of passion and complete indifference to events. But the Queen’s endurance is a testament to how far doing very little very well will get you. If only Britain’s other institutions had shown her reluctance to change. We might now have a Church that believes in God, schools that teach, or a Parliament that debates. HRH understood – unlike her liberal counselors – that at the heart of a healthy institution is ritual. The moment one undoes one’s tie or lifts one’s hem, all is lost. The smallest concession to modernity will, in short order, become a flood of change. Her Majesty has never changed. She is indefatigable. I can’t imagine life without her. I don’t want to. I am sad to be so far away from home during a rare moment of national unity. But even when I am home, I feel distant from it. Apologies to the English, but I probably don’t belong among them anymore. It’s only the idea of England that I love. The Queen embodies it because she is the last remaining ritual. My views on England are summed up in a play by Dennis Potter called, A Blade on the Feather. In a pivotal scene an aged professor tries to explain to his daughter the importance of always serving jam roll with custard. This is all England is and ever was, he says: not an ideology or an ethnicity, but a tradition. Remove the tradition and you remove the identity. The professor’s daughter laughs and he begins to cry. “There isn't any sort of England someone of my generation would think he had inherited,” he says. “Take away the pudding and the baked jam roll and the custard and there isn't very much left.” I suppose to outsiders, the professor’s talk is hollow and even effeminate (redolent of so many Brideshead boys walking around with their teddy bears). But you guys have to understand something about us English and our jam roll and custard – we have nothing else left. Of course, the thought of the Queen makes me nostalgic for certain things: Plymouth gin, Granchester, wet dogs, warm pubs, rain, women with horse whips, making love in July, boats, bowties, shortbread – even shorter tutorials – evensong, bookshops, and Barton Lake. But most of all it does make me miss the stability of the Windsors. The monarchy might still keep the English living at the status of serfs, but at least it has preserved us from the horror of the presidential primaries. (Only joking – bring ‘em on!) |

What is this?This website used to host my blogs when I was freelance, and here are all my old posts... Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed