I know that as a Brit I’m supposed to be thrilled by the games because they’re being held in “London Town,” but I just don’t get it. I can’t get excited about someone running, cycling or swimming - and while there’s a voyeuristic thrill at watching all those beautiful bodies bobbing about during a game of beach volleyball, it isn’t enough to carry me through to the rounds of shot put. Just so long as we beat the French, that’s all I need to know.

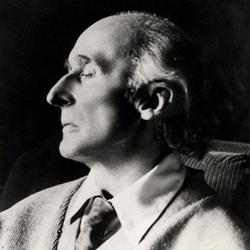

What to do on a wet summer’s day when the television is a no-go area? I’ve been working my way through the music of Frederick Delius. I discovered it after watching Song of Summer, a 1960s television movie by Ken Russell. Russell thought it was his finest film, and it’s hard to disagree. He eschews his usual stylised, operatic imagery for a stark and naturalistic black-and-white look that allows the music to speak for itself. Song of Summer finds Delius in his later years, paralysed by syphilis. He is visited by Eric Fenby, a 22-year old devotee of the composer who offers to help transcribe his final compositions. Fenby is shocked to discover that one of the giants of the English Musical Renaissance is actually a cantankerous, atheistic, poisonous old man who also can’t stand England. Fenby says, “I can't reconcile such hardness with such lovely music.” The theme speaks to a sad truth: art may be sensitive, lyrical and beautiful, but the ego and discipline required to create it can turn the artists into monsters. Several of Gore Vidal’s obituaries have made just that point.

My one criticism of the Olympics Opening Ceremony is that it didn’t include more music by Britons like Delius (throughout this post, I’ll be confusing British and English – sorry). A bigot might counter that Delius was hardly British at all; his parents were German/Dutch and he lived a great proportion of his life in France. Likewise, Holst was from a Scandinavian family, Elgar was Roman Catholic etc. The backgrounds of many of the great English composers exclude them from the Far Right’s narrow, genetic definition of what makes an Englishman (as does my own messy family tree), yet all of them created a sound that still defines the way we think of England today. Listen to Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E Minor and one is lost on the moors of Hardy’s Wessex, stumbling into the arms of Eustacia Vye.

There has been a lot of discussion about how accurate a portrayal of Britain the Opening Ceremony was. Worryingly, the debate came down to a conflict between different institutions. For the Left, the event showcased the rise of Britain from a feudal state to a socialist democracy via the NHS. The Right complained that it over-indulged social democracy and promoted multiculturalism. Both sides seem to presume that England is defined by “values.” The Left says we are all about fair play, equality, tolerance. The Right prefers individualism, freedom, national community. They’re values that mix the vague and the historically specific – and previous generations of Britons wouldn’t recognise them. Henry V (who exterminated the Lollards, crushed the Welsh and claimed the crown of France) would laugh at pluralism and free speech. Yet is he any less English for having nothing in common with the 20th century? Of course not.

Britishness is impossible to define in words or biology, which is why I wish we could’ve heard some Delius as the torches were carried into the Olympic stadium. National identity is like one of his tone poems. It’s a collection of memories, faces, places, tastes, sounds and sympathies that are summarised in one word: Britain. Anyone who happens to live here can share in it. By the same token, anyone who happens to be born here and doesn’t like it is free to define themselves as something else. To be part of a nation is like being part of a family, with the added benefit that you can join or leave as you wish. As with any other family, the members of a nation have an instinct to care for each other that goes beyond charity. We might call it duty.

So what is Britain? Traffic jams, tea, dragon flies, stormy afternoons, reggae, Surrey stone circles, bad cooking, a glissando on the strings and a rumble on the timpani. It’s impossible to define, only possible to feel. If you feel it and you get it, then you’ll very quickly fall in love with it. And you’ll discover a profound jealousy when people try to take it away from you (which is why there no more English a protest than an old lady tying herself to a tree to rescue it from demolition). If our identity is ever at risk, then it’s not from Islamic migration or too little money being spent on the NHS (we could be covered in mosques or dying from polio and still be British). It’s at risk because we don’t take enough time out of our lives to commune with it and we no longer teach our children how to experience it. We’d make a good start with compulsory Delius.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed