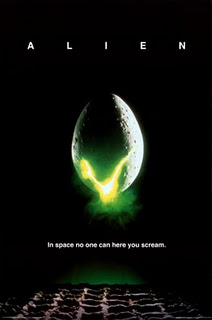

What a lucky boy I am: this week I got to see both Alien and The Thing (the prequel). It was an emotional experience, bringing up a lot of repressed memories from my childhood. Both movies are “pretty cewl” (©South Park) on a dramatic level, but they also play to themes of physical decay that mean a lot to me. Every time I see the alien pop out of John Hurt’s chest I think, “Brother, I’ve been there.”

It wasn’t until I re-watched Alien on Friday night, with chamomile tea and a pizza, that I realized quite how much it’s about sex. The sets are pure fetish. The Nostromo looks like Roger Vadim designed a womb: soft tan furnishings, gently throbbing lights, and lots and lots of hexagonals. In contrast, the spaceship that our heroes find crashed on a windswept planet is a Freudian nightmare. They enter it through an open orifice and descend through a small gooey hole into a misty pit full of eggs. John Hurt then stumbles upon a monster that latches onto his face and lays its fetus inside his stomach. One might accuse the alien of pushing his luck, but then he did pay for dinner…

When the little brute burrows its way out of Hurt’s chest, it becomes a metaphor for the nightmare of physical change. When he first reviewed the movie, Roger Ebert hypothesized that its cast is middle aged in order to emphasize that they are a group of ordinary people doing a job, not action heroes. I disagree. I suspect the director (consciously or unconsciously) cast older actors because people over 30 are more vulnerable to physical change than adolescents are. As a young adult, the things that happen to us are unnerving but healthy: they are the body evolving towards its zenith of intellectual and physical capability. After 30-or so, what was once growth becomes decay. The hair falls off one’s head and sprouts elsewhere. Muscle becomes fat; dull aches become “warning signs”. The infinite sexual possibilities of youth become desperate and less probable: one must breed ASAP, before everything dies up or falls off. Romance is dead and man is a walking advert for entropy.

When the body starts doing things that you don’t want it to, it becomes a separate personality from oneself. That theme is picked up in The Thing, which has just hit cinemas. It’s a prequel to John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982). Predictably, it’s an inferior movie. But by dint of the excellent premise, it’s okay. In this movie, the alien is a virus that replicates or consumes its victim, hides in the body, and then attacks others. We never entirely understand the nature of the thing, but it is hinted that its victims don’t know they’ve been taken over. The monster only bursts forth (with several arms, a dog’s head, and a scorpion tail) when threatened. The metaphor for the loss of control of one’s body is striking.

A chronic illness is like undergoing a personal alien invasion. The tumor that was recently discovered in my father’s throat could be the seedling of a malevolent entity. It consumes half the calories that he puts into his body, growing stronger as he grows weaker. This, combined with a nervous disorder, has left him bowlegged and tiny. Every time I see him, I recognize him less; the changes in his character suggest possession. This process is tragic, but entirely natural. Cancer is the body’s way of placing time limits on our mind’s habitation. If we all lived to 150, we would be a walking mass of tumors not unlike the creature that slithers into shot in the last reel of The Thing.

For others, the horrors of Alien and The Thing provoke a subconscious response. For me they are a trip down memory lane. When I was thirteen, I contracted an appalling case of eczema that required hospital treatment and lasted for five years. Isolated with my own carcass, I found the most bizarre and terrifying things taking place. I discovered that the skin can bleed without breaking, that sores can blister and hatch, that it is possible to scratch to the bone. Doctor after doctor unwrapped my bandages and recoiled in horror, without a clue what to do. My legs were encased in cotton wool and I began every morning with a bath of antibiotics and salt. O, how I spent so much time rubbing salt into my body – desperately trying to dry up and dust off the ooze. I was a “thing” all right: a larva jammed in metamorphosis. Oddly, the disease never touched my face. I suspect it understood that if it did, I might elicit sympathy from other human beings and someone might actually try to help. Hidden beneath the neck line, it was free to feed uninterrupted.

I am sure that it is significant that this condition arose during puberty. It convinced me that sex and physical decay are intrinsically linked. It left me with a profound revulsion for the human form – perhaps because the hours spent mapping it in hospital made me aware of its every imperfection, its every potential for disaster. Today, I am a physical Dualist. I earnestly believe that the body and soul are not only separate, but at war with one another. The soul’s quest for transcendence is constantly disrupted by the body’s sensual needs. The only way to achieve salvation is to starve the body and free the mind. Of course, living as we do in a material reality, that is impossible. So, unable to completely liberate myself, I live a dual existence between mental exercise and physical degradation. Once in a while I give my body free reign and permit it excess. When it is done “wandering the world seeking the ruin of souls”, I punish it with purgation. The best cure for a hangover is prayer and green tea.

I am a survivor of eczema. Around 18, it suddenly went away. Incredibly, I have no scars and haven’t suffered with it since. Always, there is the lingering fear that it will return; every small itch could be the beginning of a long campaign. But the experience has taught me that the body is intrinsically treacherous. Treacherous, but still a part of me: something to be negotiated with, or placated.

Watching The Alien, I was struck by the conviction that me and the “toothy one”, if given a chance, could get on rather well. I’m sure it wouldn’t want to eat me (I’m all skin and bone) and I’d make a terrible father for its little facehugger (I’d always be out with my mates getting drunk). So, instead it might tolerate me as the chronicler of its exploits. By writing about the beast, maybe I could pacify it and even own it – just as I have done on this blog post by writing about my eczema. I can imagine myself crossed-legged on its icky nest floor; one hand tapping away at the keyboard, the other tickling the gelatinous space between its numerous chins. Sci-fi yin and yang.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed