What went wrong? It’s probably not a case of choosing bad scripts – Carpenter’s early efforts were just as silly as his later ones. Nor was there a shift in theme, because all of Carpenter’s movies are about a cool dude getting harassed by some bad asses (leading to tons of gore and violence).

What did alter from 1980 to 2000 was Carpenter’s once consistent and personalized style of production. He lost his small gang of loyal actors, along with their 80s haunted eyes and sexless bodies (for an example of which, see the scarily beautiful Meg Foster). For example, no one is going to claim that Kurt Russell is sexy or believable in anything. But in Escape From New York, he embodies the classic Carpenter antihero: someone who doesn’t want to do what they have to do, but does it anyway and entirely on their own terms. No one is good or evil in early Carpenter, just trying to survive.

Carpenter’s amoral dynamics were completed by minimalist electronic music and the use of soft, dark light. These gave every scene the aura of dusk, the moment when bad stuff starts to happen. Dirty, grainy film combined with stylized acting and sound created an image that is, perversely, naturalistic. Because that’s what the West was like in the 1980s – a world trying to define itself between the pressures of 1950s conformity and postmodern liberation. Substance matched style. Hence, Halloween is set among the middle-classes in the middle of America (Illinois) in a neighborhood that has only every known peace and plenty. It is shattered by the faceless, mad terror of urban violence (killer Michael Myers) as he senselessly chops up the local teens. If Carpenter couldn’t replicate the complete vision of Halloween in the 21st century, then it’s because it’s a movie that could only be made and appreciated by an audience living in the late 20th.

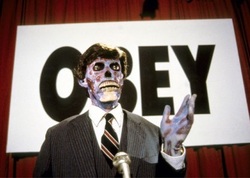

The same is not true of the film that might prove to be the most culturally significant one made by Carpenter (although it’s artistically inferior to much else). They Live (1988) is a dystopian romp which postulates that the world is controlled by aliens whose true identity is disguised by a powerful satellite signal. When our hero (yet another gritty guy just trying to do his thing) picks up a pair of magic sunglasses, he’s suddenly able to see the world as it really is. Adverts contain subliminal messages such as “Consume” and “Don’t Think.” Around one-in-ten people are exposed as alien monsters, all the more repulsive for the fact that they dress and behave much like humans. At one point a human is making love to her boyfriend when his true likeness is suddenly revealed in ugly Technocolor. The monster – unaware that he has been unmasked – innocently asks, “What’s the matter, baby?”

The movie has cult appeal for two reasons. One is its abominable script, which feels like it was written by a teenager trying to imitate Raymond Chandler. Hence: “Life's a bitch... and she's back in heat,” “The world needs a wakeup call, gentlemen. We're gonna phone it in,” and my personal favorite, “I ain't Daddy's little boy no more” (cue the pounding of a shotgun). Throw in the longest fight scene in history and you’ve got a good movie to get drunk by. My theory with the fight is that it started out scripted but then got real about five minutes in, and Carpenter kept the camera rolling. It turns nasty about the time that the white guy elbows the black guy in the groin, and the black guy cries out, “You dirty motherfucker!” Watched at two in the morning with a crate of Corona, it sounds like Shakespeare.

But the movie also touches upon a lot of late 1980s paranoia that’s still relevant today. The US economy started a post-Reagan dip towards the end of the decade that was most pronounced in manufacturing. Our meathead hero used to work in a steel mill but, like thousands of others, is driven into the cities in search of casual labor. As the Cold War ended, conspiracy theorists graduated from blaming everything on communists to blaming everything on the emergent New World Order. They Live was a little ahead of the curve – the movie makes no mention of international bankers, secret societies or the NWO. But the idea that both the government and the free market are controlled by an elite (whose orders are carried out by greedy quislings) feels very current. At one point the protagonist channels Ron Paul when he quotes, “The Golden Rule: He who has the gold, makes the rules.”

They Live doesn’t belong in the ghetto of conspiracy movies – as do Red Dawn or The Ninth Gate – partly because it’s so self-consciously funny that it defies being taken too seriously by the usual crowd of numerologists and alien abductees. But the movie also encompasses every partisan obsession, to the point that its politics are universally batty. On the one hand the subliminal messages tell everyone to consume (surely a Left-wing critique), and on the other hand the movie is concerned with both state power and the decline of the American middle-class (a Right-wing obsession). Everyone is ordered to conform, yet they are also told to put themselves first. The aliens simultaneously encourage monogamy and polyamory. The movie attacks the capitalist class in theme, but its style is redolent of the 1950s B-movies that warned of Reds under the bed. In short, The Live is open to a myriad of interpretations, which gives it a much longer shelf life than its production values really deserve.

Then again, maybe that speaks to the eternal desire to find answers to complex problems in diabolic plots. Sometimes life is so confusing and weird that the only way to order it is to imagine a conspiracy. The reason why They Live feels more contemporary than any other movie by John Carpenter is that it is the only one with a socio-political theme that extends beyond its years. It shifts the blame from humans to monsters; which is foolish, because the only real monsters in this world are human beings.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed