Hung-to-the-over and clutching at a bottle of warm Coke, I sat through most of Alien 4 today. It’s not a good movie, but it’s more interesting that the previous two in the Alien franchise (none of them come close to the original’s shock and awe). The director, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, plays it for laughs, insofar as a movie about chest-bursting aliens can be funny. Heroine Ellen Ripley has been reconstructed from a blood sample of her former self, along with an ickle baby alien insider her (“Oogie-woo, who’s a pretty boy? Don't bite. It's rude.”) The monster is removed surgically and allowed to grow into a Queen. The Queen retains Ripley’s ability to reproduce in the mammalian manner (ie, the father is down the pub throughout) and gives birth to a bouncing baby boy – who then kills his alien mother with a mean right hook. Ripley, understandably conflicted, then kills her “son” by burning a window open with her acidic blood and flushing him out into space. If all this didn’t take place in the year 2525, it could easily be a Greek myth. There’s certainly the right amount of incest and matricide.

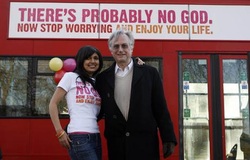

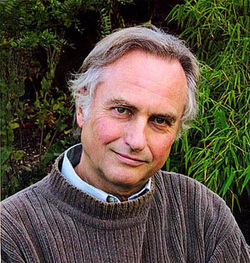

Incredibly, there’s a moment in Alien 4 when an android sees a crucifix and crosses itself. “Are you programmed for that, too?” asks Ripley. Crucially, no – for we learn that the androids have been gifted free will by their creators. One of the themes of the Alien series is how man is surpassed by the things around him. He is outlived and outpaced by animals and by even the robots that he built. That the android believes in God suggests that life doesn’t begin and end with man. Ripley is a zombie, but the android is alive and – as Ripley points out – more compassionate and therefore more “alive” than her human colleagues. Even the aliens have started to surpass us. When Ripley’s oozing baby is born, we glimpse the future. Who knows, perhaps even the chestbursters will one day sing “Nearer My God to Thee” as they fly merrily from their eggs? Androids believe in God, but scientists don’t: or at least geneticist Richard Dawkins says he doesn’t. Or does he? He can’t be sure… In a debate with Rowan Williams this week, he admitted that he is an agnostic. Dawkins said that he is only “6.9 out of seven” sure of the absence of God but that “the probability of a supernatural creator existing is very very low.” I’m surprised at the level of surprise that this statement has garnered, for he has indeed insisted many times before that he can’t dismiss the possibility of God. But what is surprising is that Dawkins can consider that possibility and then so quickly disregard it. For the possibility of God existing is far more mind-blowing than the likelihood that he does not. I don’t want to make the case for Pascal’s Wager being a determinant of faith. “Betting of God” is a shallow approach to religion and isn’t what motivates anyone but Pascal to follow one. But it’s also an odd reason to discount the existence of God, too. When it comes to theology, probability and consequence are not proportionate to another. The probability of God existing might be low but the consequences if he does are high. Vice versa, the probability of God not existing might be high but the consequences of that outcome are very low. Consider the calculations that a man makes when insuring his house from fire. If the chances of his houses catching fire are just one-in-a-hundred, he might forgo purchasing insurance because he gambles that he’s unlikely to ever need it. Yet all of us would still make the purchase because the consequences of that one-in-a-hundred accident happening are so unbearably dire. A single, improbable spark could destroy everything. Therefore, the man buys the insurance. If Dawkins is playing the law of averages, then he has to make the same calculation about God. To be sure, he only acknowledges a 1.5 percent chance that the Almighty exists. If his gamble is proven right, then Dawkins will die and suffer no consequences. But if that 1.5 percent chance comes through, the consequences are hugely disproportionate to the stakes. One of the reasons why I go to Church is that I don’t want to run the risk of spending eternity in Hell with Richard Dawkins. Even a 1.5 percent risk isn’t worth running. To re-emphasize, I don’t want to push Pascal’s Wager – but it does strike me as odd that if an intelligent man would concede that there is a 1.5 percent chance that something is true (especially when something has the weight of 2,000 years of civilization behind it), he wouldn’t explore it more seriously. It’s even odder that he thinks there is a greater possibility that there’s life on other planets. But what would it mean if that life worshiped God, too? What if the Predator is a Methodist? Or the alien is a Seventh Day Adventist? What would Dawkins say if he opened the front door and found a dalek clutching The Book of Mormon? If he wants to get rid of him, the easiest answer is, "I'm sorry, I'm a Roman Catholic..  This morning at 7am, I attended Mass at a convent two blocks down. It’s a cloistered establishment; the nuns live behind an iron grill. Before the service starts, a giant wooden screen descends from the ceiling, cutting the chapel in two and hiding the saintly ladies behind it. If you strain your ears, you can hear them gently reciting the Ave Maria through the walls. The chaplain is older than the palm trees that brush against the bell tower. He conducted the entire Mass sitting down. “I’m very tired,” he told us. “And the day has only begun.” This is what a religious life is like for most people who try to live one: quiet, human, mysterious, wonderful. I returned to my computer to discover that I’ve caused a minor storm in the community of politicized Atheists. I had spent the previous day hung-to-the-over, lying in bed moaning, eagerly awaiting the Rapture. When it didn’t happen, I flicked through the dailies to discover predictable joy at the embarrassment of a small group of religious-types. I wrote a piece for the Telegraph bemoaning the demonization of evangelicals. Sincerely, I meant to say this: “Yes, it is foolish to try to predict Armageddon, but these people are but one small segment of evangelical culture – a culture which is diverse, ever-changing, and of tremendous historical importance to America.” I concluded that it was mean-spirited to celebrate other people’s humiliation and that greater tolerance should be shown towards a movement that works tirelessly to improve people’s lives. I received one nice email from a gay evangelist; whose very existence I feel proves my point. Alas, the article was not taken quite so well elsewhere. Richard Dawkins wrote on his website, “I’m struggling to find a reason why American evangelical Christians deserve even a little respect, and I’m not struggling at all to discover that Tim Stanley merits no respect at all.” Grammar reveals a lot about a person. When it’s strictly speaking accurate but one still struggles to decipher the meaning of what has been said, you know you’re reading a sentence written by an academic. I am frustrated that Prof. Dawkins has dismissed me so easily and so cantankerously. I will only say that I hope his wife doesn’t share his view, as I’ve long admired her. She played a heroine in my favorite TV program, and wrote books about needlework that obsessed my Baptist mother during her most creative patchwork craze. Ironically, her patterns were replicated on a thousand church cushions that my mother ran through her old Singer while humming “Heavenly Sunlight”. But Prof. Dawkins’ ad hominem attack is nothing compared to this remarkable piece of class warfare. I am, according to someone I’ve never met, “a fancy little boy” (thankyou?) who is destined to be a New York Times op-ed writer (again, thankyou?). The critiques I have received are full of odd paradoxes. One blogger accused me of being “immature”. He has as his profile picture a photo of Harry Potter. People have taken offense in two prime ways. First, they don’t agree with my reading of history that evangelicalism has shaped American democracy. Actually, that’s a no-brainer. The Puritan influence is up for debate; while some historians see them as inflexible theocrats, others argue that their surface authoritarianism was bound by an inner quest for personal enlightenment that was freely obtained and not coerced. But on the influence of the first and second Great Awakenings, historians are at one in acknowledging that evangelicalism shaped social egality, notions of citizenship, and the party system. [I said that Jonathan Edwards was the “greatest” American theologian. Mea Culpa, that’s my personal prejudice. But it’s not unique]. I would urge those who care to get a copy of Richard Carwardine’s Evangelicals and Politics in Antebellum America (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1997). It’s the definitive book on the subject and you’ll read how everything from mass participation to female emancipation finds some root in inter-evangelical debate. The positive role played by evangelicalism was felt during the 1960s Civil Rights movement and is still there today in campaigns for prison reform and debt relief. True, some denominations opposed all those things. But my argument was never that evangelicalism was everywhere and always good – just “complex and nuanced”. Second, some readers have inferred – disingenuously – that I think religious people are charitable but atheists are not. Again, the point of the piece was not to attack atheism as a philosophy but to defend evangelicals as human beings. I do think it is in poor taste for some atheists to celebrate the misery of those who thought they’d be raptured but weren’t. (That said, I’m quite glad I wasn’t. I’m not ready to face my bank manager or my priest, let alone God.) This second point goes to the heart of a lot of the criticism my piece received: my critics hadn’t actually read it. At least, they read it myopically – picking out a single sentence (or even a couple of words within a sentence) and extrapolating from a handful of syllables that I favor witch burning and table-wrapping. There is an excellent movie due out soon called Patriocracy. It argues that the national conversation about politics has become debased by extremism, of a blanket refusal to even hear another’s argument. I agree. True, I wrote a piece that had an obvious agenda. But it was filled with equivocation and cowardly sub-clauses, things that I always put in my writing because I’m careful not to reduce everything to an idée fixe. Yet the anger of the debate about religion seems to have blinded some people to subtle argument, and the instantaneous nature of blogging means that – rather than sit down and construct a thoughtful letter as in days of yore – they are able to type “Fuck you, you posh twat”, press return, and publish it within seconds. That’s all fair enough, and I don’t really mind because that’s what I signed up for when I started blogging for the Telegraph – a paper whose very existence drives some hipsters into intensive yoga. But I am disappointed that Prof. Richard Dawkins – a professor of Oxford, no less – is capable of similar yobbery. He is a fellow academic after all, and he probably knows just how highly we prize our “respect”. It is our economic and emotional sustenance, and I would never deny it to anyone as easily as he has refused it to me. |

What is this?This website used to host my blogs when I was freelance, and here are all my old posts... Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed