|

Footage of “Mrs Margaret Slee, president of America’s Planned Parenthood” from 1947, in which she urges Europe’s women to stop breeding. It’s a strange mix of charming and frightening.

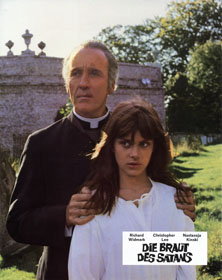

Across the world, the Catholic Church is under siege. The Pope is protested wherever he goes, Catholic dogma is challenged by the New Atheism, and sex abuse scandals have diminished the reputation of the clergy. But hope can be found in the most unlikely of quarters. I've found it while re-watching a mountain of Seventies horror movies (like the marvellously kinky To the Devil a Daughter, pictured on the right). The shifting fashions of this particular genre reveal that public opinion is very fickle. In the 1970s, priests on film swung from being perverted guardians of the old order to mystical prophets of the next - sometimes in the intermission between double-bills. In the 1960s, the Catholic Church fell afoul of the thirst for personal liberation. The reforming Catholic council of Vatican II shattered the Church’s confidence in its mission, while secularization – spurred on by liberalism triumphant – swept Europe. These changes were only felt at a popular level in the 1970s, when sexual freedom and a declining respect for authority finally trickled down to the masses. For millions of souls it was a heady age full of lingering regrets, like experimenting with LSD or voting for Jimmy Carter. It was inevitable that the anti-clericalism of the decade would appear on film. Seventies horror cinema – best viewed with a keg of beer and lots of Monster Munch – is full of scathing critiques of the Catholic Church. Some of them are rather good. A typical example is Lucio Fulci’s Italian production Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972), in which a Catholic priest murders little boys before they can “come of age”. The priest is motivated by an obvious sexual lust for his charges, as expressed in a speech he gives while falling off a cliff: “They grow up. They feel the stirrings of the flesh. They fall into the arms of sin, sin that God easily forgives yes: but what of tomorrow? What sordid act will they commit? What sins will they enact when they no longer come to confession? Then they will really be dead, dead forever, dead for all eternity. They are my brothers … and I love them.” The priest’s killing spree is Lucio’s personal metaphor for a Church that won’t accept the social changes of the 1960s and let its congregation grow up into mature, self-governing adults. The message implied by having Barbara Bouquet appear naked throughout the entire movie is less clear. But closer study of the horror genre shows surprising nuance in the handling of priests. Two movies that deal thoughtfully with priesthood in an age of flairs are What Have You Done to Solange? (1972) and House of Mortal Sin (1976). The latter was directed by the brilliant Pete Walker, who had previously made some surprisingly conservative horror movies satirizing social reform (in one of them a cannibal is given an early release from prison for good behavior and, predictably, becomes a recidivist). House of Mortal Sin stars the wonderful Anthony Sharp as Fr Meldrum, the ultimate Seventies symbol of Church hypocrisy. Meldrum’s a traditionalist priest who refuses to say the reformed Vatican II Mass. He tapes confessions and uses them to blackmail parishioners into attending rough therapy sessions at his house where he shouts at them for enjoying sex too much. We learn that his mother forced him into the priesthood and refused to let him marry his childhood sweetheart. Sexual repression twisted into religious mania and it’s not long before Fr Meldrum’s off killing buxom young wenches in a variety of symbolic ways (strangled with a rosary, poisoned with a wafer etc). So far, so liberal a critique. But at the emotional heart of the movie is a younger priest called Fr Bernard who has shacked up with Stephanie Beacham (well done, sir!). He’s toying with leaving the Church and parades all sorts of hip opinions about sex and drugs. Drippy Bernard is established by Walker as the hero, the man always on the brink of doing the right thing. But at the end of the movie, Fr Meldrum convinces Bernard to help him cover up the murders. He reasons that if the public knew what was going on, faith in the Church would collapse and all its good works would be diminished. Walker’s movie may be scathing of moral traditionalism, but he is equally condemnatory of Bernard’s cowardice and cronyism. The message: the sins of the past are excused rather than corrected by the timid liberalism of the present. Given the willful blindness that many “progressive” bishops demonstrated towards sexual abuse in the decades to come, it’s a remarkably prophetic vision. The more nuanced What Have You Done to Solange? argues that the problem with the Church isn’t hypocrisy: its moral emasculation in an age of excess. The eponymous Solange is the daughter of the headmaster of a Catholic boarding school. At the start of the movie she’s a gibbering, idiotic wreck and no one seems to know why – or care. The school’s gym teacher, Enrico, is having an illicit fling with an underage student (but it’s okay, because both of them are hot). The two are cavorting in a rowing boat when they witness the brutal murder of one of the schoolgirls. Later, Enrico’s sexpot girlfriend is drowned in the bath for what she saw, forcing him to go on the hunt for the killer. Director Massimo Dallamano encourages us to think that it’s one of the priests at the school behind the kinky massacre. A rosary is glimpsed and it is implied that the killer picks his victims whilst hearing their confessions. But Dallamano has a surprise for us. Enrico realizes that the villain isn’t picking on random girls but rather on former friends of Solange. At the film’s climax, he discovers that all the victims were involved (very willingly) in a sexy sex ring. Solange got pregnant and the schoolgirls forced her to have an abortion, performed with rusty implements on a kitchen table. Solange was driven mad by guilt. Her father, the headmaster, took it upon himself to avenge her by slaughtering everyone involved. Dallamano implies that the Church is partly at fault for not having chastised the schoolgirls and enforced moral order. The priests on screen are nice enough fellows, but presented as tired and confused; the schoolgirls regularly skip Mass and no one notices. The headmaster represents an outraged laity that must take order into their own hands. Given the awfulness of the abortion scene, the audience is prompted to sympathize. What Have You Done With Solange can be read as a sort of prolife response to It’s Alive!, a traumatic movie about a baby born with a taste for human flesh. Solange and Ducking really belong to the early 1970s, when Freud’s influence was still felt in Europe's studios. But something changed in the horror genre mid-decade. Take the movies of Dario Argento, the master of Italian schlock. His early efforts (Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Deep Red) feature human villains motivated by sexual angst. By the end of the 1970s, he was making movies like Suspiria and Inferno, in which the culprits are witches. The popularity of the theme peaked in the mid-1980s with two movies he co-produced called Demons and The Church. Both feature literal demonic infestation, usually beaten back by cool black dudes on motorbikes. In the course of a decade, audience tastes had gravitated from Hitchcock to Edgar Allen Poe. That slow change was reflected in the wider depiction of priests on film. In 1973, Warner Bros released The Exorcist. The movie depicted two priests; one modern and skeptical, the other a traditionalist mystic. It is the mystic, with his peculiar Latin rites, who is revealed to be correct about the demon possessing foulmouthed child actress Linda Blair. The hysteria surrounding the movie helped revive the Church’s reputation as a force for good. Its medieval understanding of pure evil, which seemed so anachronistic in the 1960s, was now terrifyingly hip. The release of The Omen in 1976, in which Satan is incarnated as a child, further underscored the triumph of Catholic mysticism. The movie features a batch of apostate priests, but there’s no doubt that it is Catholic dogma that holds the key to repelling the Antichrist. Both movies coincided with the American Fourth Great Awakening and a worldwide revival of religious evangelicalism that offered an escape from the economic miseries of the late 1970s. Alas, the Moral Majority typically campaigned against horror movies on the grounds of violence or explicit sexuality. They missed a trick. Many of the video nasties they opposed were infused with the religious sensibilities of the era. If only they had forced themselves to watch them, they would have realized that most were recruiting films for the Catholic Church. Of course, individual movies and their directors don’t speak for the entirety of mass culture. But the improving screen image of priests does hold out hope for our current generation of clerics. History and culture don’t always progress forward; shocks to the system can spark social revolution, but they can also help resurrect orthodoxy. In the sexy, violent world of 1970s horror, everything old was new again.  It’s a pity that the riots broke out when they did, because I was just starting to fall in love with England again. I stepped off the plane at Heathrow after three months in Los Angeles and noticed, for the first time in years, how pretty Albion is. England’s beauty is not like America’s (harsh and empty) or Europe’s (exciting and big), it is small and perfectly managed. Like our food, it is quite plain. We drove home past miles and miles of patchwork green and yellow fields. I lay on the backseat and watched the tops of the telephone polls and the cotton-wool clouds go by, and I was very happy to be home. Now it is a perfect Sunday, spent home alone at my parent’s place in West Kent. My father has a heart condition that this morning caused his lips to swell. He looks like Mick Jagger. My mother rushed him off to hospital and I had the house to myself. I opened all the windows, put on some Beethoven, and lit a cigar. I suppose I am lucky to have won the lottery of life and been born an Englishman. How other races survive without the comforts of Radio 4, shortbread, Marmite on toast, warm beer, Betjeman, and Viz, I cannot imagine. I don’t regard any of these things as a signifier of race or class. My own politics has changed, but my ideals have remained constant. I wish every Englishman could live like this: it is their inheritance, regardless of origin. I believe that beauty and ugliness are lived in balance, which is why last week’s riots were less of a shock to me than they might have been to others. I am angry, of course. I yearned to go to London with a baseball bat and dish out some justice of my own. There was a window last week when it was possible to guillotine thieving children in public and no one would have minded. That window has closed and the liberal backlash is upon us. We will now have to consider “what is wrong with our society?” The answers will range from “too little money” to “too much money”. But I don’t think there anything wrong with England that can be understood in material terms. We’re simply human beings, and human beings are not nice animals. The English think they are nice because they are obsessed with good manners and etiquette. But these are artificial things, not genetic dispositions. Throughout the centuries, we have used to them to suppress or hide our latent violence. The Japanese did the same, burying their brutality beneath ritual. In Blighty, we don’t talk, we don’t complain. We eye each other carefully over the kitchen table; take notes, record slights, plot revenge. Anecdotal evidence from football matches and Saturday night punch-ups testifies to our nasty nature. The English drink like they don’t want to live. Unleashed from good manners by booze, we are monkeys. I was very amused by this post written by an American on the nightmare that is contemporary England: “I accidentally broke into a queue once and thought I might die from a thousand umbrella pokes. I’ve felt under physical threat at Gatwick by a man who thought my concern about making my plane was an accusation of him of something. England is the only country in which I’ve been pursued by a man in a car saying “I am going to get you.” Where I’ve lost many packages on the train or in a crowd when I was pushed against, where a taxi driver has stolen from my bags when he got them out of the car, where I’ve had a friend brutally beaten by an intruder where all the undergraduates in her building ignored her screams because they didn’t want to get hurt … So the idea is that there are inexplicable little outbreaks that are almost wholly ignored, until they come together.” Et voila, the August riots. Don’t believe that a nation so anally obsessed about putting the milk in the cup first could kill indiscriminately? Why, the list of English atrocities in endless. In 1919, our fine military men gunned down roughly 1,000 Indians at the Amritsar Massacre. I’m sure we didn’t get a single drop of blood on our nice white collars. During the 18th and 19th centuries, we carried out a systematic genocide of the population of the Scottish highlands. Farms were burned down and thousands of people starved to death or driven abroad. In the 17th century, Oliver Cromwell carried out a similar decimation against the Irish as part of our civilising process over there. In the 15th century, the revolt of Welsh prince Owen Glendower was put down with predictable brutality. I remember reading about it in school books and blanching at the stories of Welsh women killing wounded English soldiers by cutting off their genitalia and stuffing it in their mouths. Fanciful or not, the idea speaks to an innate brutality in the British population. The bourgeois cult of good manners that erupted in the 18th and 19th centuries – when erotica was re-classed as pornography, prisons replaced local jailhouses, debtors were isolated, and the unwashed masses deported wholesale to Australia – created the mythical reserve that still represses our passions today. This is a pessimistic message, but not without hope. Redemption from original sin is possible and we can all find it if we ask for it. But the first step towards redemption is admitting guilt. And the English myth of good manners prevents us from doing that: we just won’t admit that we are capable of violence. Our people, we insist, are the politest in the world – our soldiers the most orderly, our policemen the most courteous, our villains the most honest, our teachers the most hardworking. These precious fantasies cloud our vision. Meanwhile, the grip of good manners is slipping and bad behavior is on the march. We don’t even adhere to the cultural norms that we define ourselves by. The British are a dog unleashed. What we don’t need is reactionary state violence. The thirst for it is natural, but its actualization never is. In his play Marat/Sade (properly titled, The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade), Peter Weiss explored two revolutionary prerogatives. The first, represented by de Sade, is the tendency to spontaneous popular violence. The second, taking its lead from the first, is Marat’s brand of social justice brutally enforced by the state. De Sade initially supported Marat’s Terror, when it was random and democratic. He lauded the looting of the rich. But when the state took the mob’s place and set up committees to process enemies of the revolution wholesale, de Sade was disgusted by the turn towards dispassion. The guillotine was swift, clean, inhuman. To quote de Sade, as interpreted by Weiss, the urge to destroy is natural but state terror is not: “Haven't we always crushed those weaker than ourselves? Haven't we thrown in the throats of the powerful with continuous villainy and lust? Haven't we experimented in our laboratories before applying the final solution? Man is a destroyer. But if he kills and takes no pleasure in it, he’s a machine. He should destroy with passion, like a man.” De Sade recounts a romantic death by torture, murder, and final absolution. Then he compares it with the ruthless banality of the modern, totalitarian state: “Now is all official; we condemn to death without emotion. There is no singular, personal death to be had. Only an anonymous, cheapened death that we could dole out to entire nations on a mathematic basis until the time comes for all life to be extinguished.” We don’t want this, but it’s what we’ll get if we cede public anger to the government. What we do need is to correct the imbalance between the reality of human nature and public policy. However that is done, it must involve a realization that we’ve grown apart from England as a place. Life lived close to the land is lived in sympathy with the cycle of birth, sex, death, and rebirth. Life lived away from the land has to be ordered by good manners because it is so unnatural and disturbing. Rats confined in a small space will tear each other apart. Living without myths doesn’t mean living without beauty. There is a real England beyond all that nonsense about stiff-upper-lips and Sunday best. It is the England of the patchwork of green and yellow that I observed from the car. It is England real and eternal for it exists in one’s hand when gripped as a lump of sod or a blown like a fart as a blade of grass betwixt finger and thumb. To quote Edward Thomas, on leave from the slaughter in France: “Often I had gone this way before:/ But now it seemed I never could be/ And never had been had been anywhere else;/ ‘Twas home; one nationality/ We had, I and the birds that sang,/ One Memory.” August is leaving and Autumn will come. The leaves will fall, the green and yellow will become brown and red. Keep calm and carry on, Britons! For the England you have always known is still beneath your feet. PS: the picture is a piece of Gin Lane by Hogarth, depicting a drunken Englishwoman cheerfully abandoning her child.  As a historian of the US, the riots in London made me think instantly of the urban disorder in America in the 1960s. There are big differences: size, scale, and lack of political motive this time around. This is not the right moment to plug a book, but I noticed when researching my forthcoming biography of Pat Buchanan that there were three different reactions to the disorder of the 1960s. Two – Leftwing pandering and Rightwing populism – were on display in this nice vignette from the 1968 Chicago riots. The local police had horribly over-reacted to the presence of 10,000 antiwar protestors during the local Democratic Convention, using nightsticks and tear gas to dispel the largely peaceful crowds. The demonstrators gathered in Grant Park, across from the hotel where the conservative pundit Pat Buchanan was lodging. He stayed up all night with the Leftwing writer Norman Mailer, drinking cocktails and watching the fight down below. The city had imposed an 11pm curfew on the demonstrators and when they failed to move, the police charged them with teargas and truncheons. Mailer leant over the balcony and screamed at the cops, “Pigs! Fascists!” Buchanan leant over and shouted, “Hey, you’ve missed one!” Those were the two responses to the crises of 1968 that most people are familiar with, and both are getting a big play in London 2011. In the 1960s, several conservative populists called for a take-no-prisoners answer to urban chaos: no recognition of supposed grievances, 100% support for the police, and zero tolerance for offenders. Presidential candidate George Wallace promised to hand the streets over to the cops for 24 hours, all civil liberties suspended and no questions asked. Having just witnessed my own capital city be looted by thugs and vandals, I feel considerable sympathy for this position. One’s first instinct in the midst of criminality is to go all Rambo. A good friend asked the question on Facebook, “Where is Charles Bronson when you need him?” Leftwing commentators in the 1960s expressed far greater sympathy for the rioters than what one might find today. The Kerner Commission of 1968 blamed the disturbances entirely on racism and poverty, with little consideration for personal responsibility. It concluded that “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white – separate and unequal”, and proposed massive federal spending projects as a solution. That view, incidentally, is still popular within my own field of historical research. The consensus within the academy is that the disorder of the 1960s was a legitimate response to white racism and an unjust war, while the stunning popularity of conservative politicians like Wallace, Buchanan, or Ronald Reagan reflected an underlying mainstream fascism. What is forgotten about 1968 is that there was a “third way” response to the violence, and it had a big constituency. It was the approach taken by Democratic presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey: toughness informed by compassion. Humphrey was a liberal before the term became submerged within radical Leftwing discourses in the 1970s – before it became synonymous with socialist economics and identity politics bullcrap. Nor did it have anything to do with obscure British philosophers: Smith and Mill probably sounded like undertakers to Hubert. Rather, it was a politics shaped by the misery of the Great Depression and the violent grandeur of the Second World War. Humphrey’s liberalism was tough and sinewy. He loved his fellow man, but he understood that part of love is censorship and reform. Man is born in sin: people used to get that. When he accepted his party’s nomination in Chicago 1968, the same week that Mailer and Buchanan watched the cops and demonstrators duke it out in the street, Humphrey opened with the prayer of St. Francis of Assisi: “Where there is hatred, let me sow love; where there is injury, pardon; where there is doubt, faith; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light.” Then he said, “Rioting, sniping, mugging, traffic in narcotics and disregard for law are the advance guard of anarchy and they must and they will be stopped. But may I say most respectfully, particularly to some who have spoken before, the answer lies in reasoned, effective action by state, local and federal authority. The answer does not lie in an attack on our courts, our laws or our Attorney General. We do not want a police state, but we need a state of law and order. And neither mob violence nor police brutality have any place in America.” It was a complex formula, perhaps too nuanced for the angry spirit of the age. But it balanced what many citizens were looking for: a definition of law and order that keeps in check both the criminal individual and the over-mighty state. Humphrey went on to say, “Nor can there be any compromise with the right of every American who is able and who is willing to work to have a job, who is willing to be a good neighbor, to be able to live in a decent home in the neighborhood of his own choice … And it is to these rights – the right of law and order, the right of life, the right of liberty, the right of a job, the right of a home in a decent neighborhood, and the right to an education – it is to these rights that I pledge my life and whatever capacity and ability I have.” What Humphrey meant was that law and order and social reform are not contradictions as the Marxist Left would have us believe: they are two sides of the same social contract. Peace guarantees the opportunity for progress and progress irons out the iniquities that spur disorder. It’s a forerunner of that blunter paradigm, “Tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime”. For those who, frankly, want to see some criminals get a good thrashing but who also don’t want to give up on the dream of urban renewal, this is a powerful promise. It was popular enough in 1968 to take Humphrey to within one percentage point of winning the presidency. As we have come to expect, Britain’s political leadership has been singularly lacking throughout these riots. A few have offered jingoisms, while a former mayor has unwisely suggested that the hoodlums need love. There is a space – a wide vacuum in fact – for a reasonable statesperson to ask, “Can’t we all get along?” Most voters are conservative in that they want peace in the streets yet liberal in that they don’t want to use water cannons to get it. One solution is transformative leadership. Robert Kennedy offered something of that when he spoke in Indianapolis on the night of Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination. He said, "What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness, but is love, and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black." He asked the crowd to go home and pray, and they did. Indianapolis was one of the few major US cities that didn’t experience riots that night. I pray that a similar recourse to reason is still possible in this crisis. In the absense of decent leadership to provide it, I shall be getting grandpa's shotgun down from the attic. To quote Pat Buchanan when asked his response to new federal gun controls: "Lock and load". |

What is this?This website used to host my blogs when I was freelance, and here are all my old posts... Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed