However, I was surprised by my old priest, Fr Ray Blake of Brighton, comparing The Shard to the Tower of Babel in the Bible. Quite what he means is hard to tell because the meaning of Babel is itself opaque. In the story, a united humanity builds a tower, “whose top may reach unto Heaven.” God sees the tower and says, “Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do; and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech. So the Lord scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city.”

There are two ways of reading this story. One is that is simply explains why we speak different languages – man reached a certain point in his civilization and God decided, in his infinite wisdom, to mix things up a bit. Babel is thus an “origin myth” (which could be literally true or fable) that has no more moral weight than all those interminable lists of “begats” that we get in Genesis. This God seems rather capricious.

An alternative explanation is that man was punished for the sin of pride. He constructed a tower in celebration of himself (it was not a temple) and from manmade things. Realizing that man had the capacity to stop worshipping him and start worshipping themselves, God evens the playing field by scattering humanity across the continents. Later, Christians believe, God offers Christianity as a way of reuniting ourselves around the divine made flesh. Of course, we pretty much screwed that up, too.

So is The Shard the new Tower of Babel? I wouldn’t say so. It’s certainly built for the purpose of man’s enjoyment rather than worship of God, but then Christ is healthily contemptuous of such things and urges us to render material them unto Caesar anyway. “You can have your consumerist, wealth-obsessed civilization and keep it,” the modern prophet might say. “We are more interested in what happens next.” Critics of The Shard should adopt the Franciscan approach and wander through the opulent city in the rags of the poor. Be in the world, but not of it and chuckle at the follies of the rich.

But what the Tower story does remind us that the antithesis of monotheism – Judaic, Christian or Muslim - is worship of man. That might seem like a harmless assertion, but actually it contradicts the modern impulse to put man first, be it for benign or malign reasons. You find that in theology, where rules and teachings have been adapted to make it easier to be a believer. It sometimes feels like my own Catholicism only encounters orthodoxy for 60 minutes on a Sunday morning. The rest of the week is a constant negotiation over what is and isn’t the right thing to do.

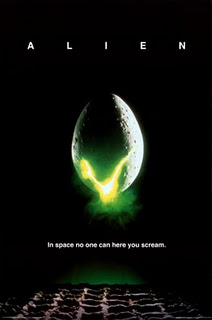

Within civil society, there was a trend in the 20th century to see man as the genius of his own invention, someone who could command his own destiny. Disease, environmental catastrophe, recession and the pitiless logic of war indicate that he cannot. Mankind is primed for self-destruction: only this species would behold a wonder like the split atom and then use it to murder hundreds of thousands at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Love man – yes. But don’t worship him. It’s the failure to recognize a moral order beyond what men want that leads to the collapse of civilizations.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed