But I’m pleased that I found time to read Paul Lay’s History Today – And Tomorrow. It’s a fine book that reminds us that history is the “king of disciplines,” for it synchronizes all others and turns disparate studies into a coherent narrative of the human drama. It is good to be reminded of how great we historians are.

Paul makes two points that I think are particularly potent. The first is that history is not a comfortable discipline. A lot of what one sees in popular history is tawdry nostalgia. From the endless History Channel documentaries about being a Spitfire pilot to the insufferable BB2 shows about life in a Georgian household (“Look ma – they made their own cheese!”), history has become something that affirms rather than challenges. Commissioners are terrified of anything that a modern audience will not instantly recognize, so they only produce that which “speaks” to them. That’s why domesticity is such a popular theme, or the history of the last forty years. When did BBC4 last venture into political territory that wasn’t to do with Harold Wilson or Margaret Thatcher?

Dramatists must be given credit for throwing their nets wider (The Tudors, The Borgias) but even these shows invariably give ancient characters modern sensibilities. Take the dreaded Downton Abbey. At the center of Downton is the lie that the Edwardian household was like a modern extended family: open, warm, democratic. It was not. In fact, African-American slavery was arguably a more intimate type of service than the manorial system. Don’t get me wrong – it was sustained by violence. But most historians of slavery now argue that it was surprisingly geographically unsegregated (it was common, for instance, for slave and free children to play and be nursed together). By contrast, in Edward England social relations were simply impermissible and if any servant spoke to an employer in the way that they do in Downton, they’d have been sacked … or worse. Downton Abbey has nothing to do with the past and everything to do with today. Whenever the English are in trouble, they retreat into nostalgia and reflect upon their present circumstances by looking backwards. They see at history through the dark glass of their own context and conclude, "We are, and we always have been, bloody marvellous."

Instead, history should be honest and ugly. It ought to present the facts “warts and all” and strictly on the terms of the people who lived it. If there is a benefit to doing this, it is to understand that other people in other times are capable of viewing the world differently – and not just because they are ignorant or savage. There is a tendency – I’d call it cruel – to presume that because everyone born before 1940 didn’t think that the Earth circles the Sun or that constant uninhibited sex is a God given right, they were all ignorant peasant scum; worthy only of being a lesson in how stupid talking monkeys can be. That isn’t to say that we should suspend our moral faculties when regarding the past: the folks living there were sometimes scathing in their judgement of it (consider the foundational ethics of Socrates, Thomas Moore, Mary Wollstonecraft, or Sojourner Truth).

But we must sink ourselves into the sanctity and the depravity of history, if only to understand what man, under certain circumstances, is truly capable of. Paul Lay expresses this better than I can in the Huffington Post: “History, at its best, calls everything into question. It offers no comfort, no shelter and no respite, it is a discipline of endless revision and argument. It forces its students to confront the different, the strange, the exotic and the perverse and reveals in full the possibilities of human existence. It is unafraid of casting its cold eye on conflict, both physical and intellectual.”

Second, the study of the past teaches humility. The great sin of modernity is arrogance, and it is sustained by two false propositions – 1) We can make things better and 2) No one has tried this before.

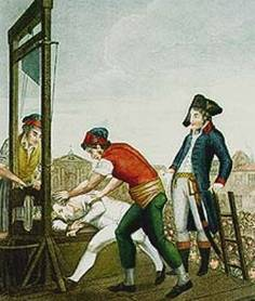

It is correct that we now have the technological resources to screw things up on a truly industrial scale, but we are far from the first people to attempt to improve man’s lot. History shows that these efforts quickly end in tyranny. Invariably, it begins with an effort to eradicate the past – precisely because it usually offers sound argument against change. The French Revolution had its Year One; the Soviets had their Historical Determinism. Sweet requests for social justice in the New Age then become violent demands for the keys to the kingdom, unlimited by the precious checks and balances that traditional culture had hitherto exerted. Progress made by mobilizing the people has always turned out to be a authoritarian disaster. We can, as individuals, redeem ourselves. But social reform of the type that modern states have invested in is just violently rearranging the furniture.

Nor does everything stay the same. Today in the West we are still living as if history is at an end. Liberal democracy and free markets are here to stay. If we are honest, we look upon the Chinese or Brazilian models of capitalism with contempt (Niall Ferguson looks upon the former with terror). The Islamic world is a land of 14th century barbarians and Africa – epitomized by Joseph Kony’s child army – is irredeemable. The West regards its backyard with as much loathing and incomprehension as it does the Tudors and the Borgias. Our inability to understand other people is made worse by a lack of sympathy for our own history.

And yet, we show the exact same arrogance of the Victorian British who presumed that the sun would never set on their own empire. As Paul Lay reminds us, “[History] has no end, as the benighted Francis Fukuyama discovered when the permanent present ushered in by the fall of the Berlin Wall came crashing down on September 11th, 2001. History opposes hubris and warns of nemesis. It doesn't value events by their outcome; the Whig interpretation of history expired long ago.”

Paul would probably stop there, but I’ll throw in a little postmodernism. The great irony of the West’s attachment to its liberal system is that this system is so fragile that it is arguably already gone, swept away by war, recession, the erosion of the Good Society, and the tyranny of the senses. We are now living and perpetuating a myth, sustained by a deliberate ignorance of the alternatives. “Everything that we see or seem is but a dream within a dream.”

As Dennis Kucinich would say, “Wake up America!” I’ll never forgive Ohio for voting that man out of office.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed