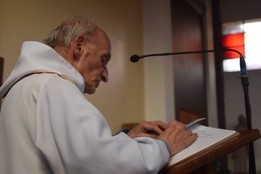

As Damian Thompson writes, the murder of Christians in the Middle East is a regular occurrence. The slaughter of Fr Jacques Hamel, 85, probably made the headlines last week because he was killed in France. I don’t say that to downplay the horror. On the contrary. We each identify best with those who look the most familiar – and the idea of terrorists targeting the kind of church I regularly attend feels like an invasion of my own private temple.

That said, Christianity was made for this. It began with an act of self-sacrifice upon the cross. The word was spread through the example of slain evangelists – St Peter crucified upside down, at his own request, so that he wouldn’t imitate Jesus. It is a rare faith that rejects conquest by the sword not only as immoral but as a contradiction of the dictum that belief is a matter of conscience – that faith must be freely chosen. Ours is a very Jewish faith, a logical and intellectual faith that is routinely tested. The Israelites were stolen from their lands and left to wander the desert. The psalmist says: “Out of the depths I cry to you, Lord./ Lord, hear my voice./ Let your ears be attentive,/ to my cry for mercy.”

Christianity is a history of the rejection of violence, a progression towards peace. God told Abraham that it wasn’t necessary to sacrifice his son for him. Jesus taught us to turn the other cheek. The Messiah’s death upon the cross is a sacrifice that washes our sins away, and the Lamb of God is offered in our stead. At the Catholic Eucharist, that sacrifice is re-enacted and the bread and wine are transformed into the flesh and blood of Christ (no wonder the Romans thought we were cannibals). Martyrdom means “to witness” and Jesus witnessed loneliness, pain and death. Christians who suffer thereafter are witnesses to the love of Jesus. Those who die because of their faith, such as Fr Hamel, are rewarded in Heaven.

But there are small acts of martyrdom that occur every day around us. I noticed that Fr Hamel was well beyond the age of retirement – and, regardless of personal enthusiasm, there are plenty of priests who are compelled to go on working because vocations are so dramatically down. I knew a priest in Los Angeles who drove between Compton and West Hollywood several times a week to say Mass, into his eighties – and it wasn’t out of choice but duty. Often he was greeted by a near-empty church. The church was conspicuously light on attendance the day that Fr Hamel was attacked.

I know another priest who never wears the dog collar when out. Why? Because a couple of weeks after ordination he was sitting on the London underground in full uniform and someone called him a paedophile. The embarrassment has clung to him for years. A lot of priests tell me they’ve experienced something similar, or else that the collar makes them a magnet for demands for money, violence or juvenile satirists. Hardly surprising given that the Church is presented in the media as hypocritical or sexually perverse or rolling in money. Rolling in money! I bet Fr Hamel didn’t have two sous to rub together. Priests live poor lives, often marked by loneliness.

And yet still people choose to do it. Why? Partly because it’s not all that bad – I don’t want to put anyone off. No other job offers the chance for such emotional and spiritual development. It is like joining a glorious army with all its possibilities for fun, travel and adventure. Except that this army uses words rather than weapons.

Moreover, suffering is part of the job description. How else can one describe a vocation that demands celibacy and passionate service of the community as a way of life? Suffering is part of everyone’s DNA, of course. We are born screaming, we often – alas – go out screaming, too. But the priest who stands at Mass “in the person of Christ” aspires to be Christ-like and offers himself up as a sacrifice, too. Witness Maximilian Kolbe, the Polish friar who volunteered to die in place of a stranger at Auschwitz. John Paul II, who bore the suffering of old age with awe-inspiring dignity, called Kolbe: “the patron of our difficult century.”

John Paul II said that Kolbe “won a spiritual victory like that of Christ himself.” That’s something the Islamist killers could never have understood. Their act – hateful, false, heretical – was, in the words of Pope Francis, “absurd”. Fr Hamel’s death was a victory. Yes, a victory. His life has left a glorious example. He died witnessing the love of Christ. And the arrival of Muslims at Mass the following Sunday holds out the hope that it will catalyse defiance and French unity. France must not allow the Islamist fringe to tear it apart. It must fight hate with love, and with radical acts of trust.

That said, let us not be stupid. We are vulnerable. States have a duty to protect us. We need to talk honestly and openly about the pernicious influence of Wahhabism. Integration at some level is not happening, and when separation translates into violence then the wider community obviously has a right to demand conformity.

Those of us who are Catholic need to acknowledge our own failings. Fr Hamel’s death has not just frightened me but shamed me. Am I prepared to die? Will I give what I have for the faith? Have I done nearly enough to support those priests who suffer every day for the laity? No, no, no. Shame on me.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed